I have been a chronic pain sufferer for around 24 years. My condition does not define me, but has had, and continues to have, a significant impact on my life. It is something I have had to learn to live with, and to manage, as best I can. It is very unlikely to ever go away, it is long term, and has a substantial, adverse effect on my ability to carry out normal day to day activities. As such, chronic pain, along with many other conditions, is recognised as a disability under the UK Equality Act of 2010. Furthermore, it is considered an invisible disability, in that it is not immediately obvious to others.

A recent UK Parliament Research Briefing; Invisible Disabilities in Education and Employment, estimates that 70 – 80% of disabilities are invisible. The briefing describes how;

Those with invisible disabilities may experience attitudes of disregard and disbelief because they defy stereotypes of what people perceive disability to look like. In a 2021 survey of people with energy-limiting conditions, 85% reported a lack of understanding and 65% reported disbelief of their impairment…..People with invisible disabilities also report facing criticism when trying to access facilities designed for disabled people.

Those with invisible disabilities may experience attitudes of disregard and disbelief because they defy stereotypes of what people perceive disability to look like. In a 2021 survey of people with energy-limiting conditions, 85% reported a lack of understanding and 65% reported disbelief of their impairment…..People with invisible disabilities also report facing criticism when trying to access facilities designed for disabled people.

Leading UK disability charity, Scope, also report that they often hear from disabled people who are not believed or are even accused of faking disability.

Unfortunately, it’s all too common to face rude or invasive questions about support needs and adjustments. Or even to be on the receiving end of nasty looks and comments when using blue badge bays or accessible toilets.

Sadly, the recent UK Morrissey tour of July 2023, demonstrated for me that all of this is indeed the case. First, let’s try to unpick the master class that was given in what not to say to someone with a chronic pain condition. Unfortunately, I have had to repeatedly face these types of comments over the course of the past 24 years.

You seem fine

Chronic pain sufferers have become expert at hiding their pain. We simply can’t spend all our time rolling around screaming, and we generally have the good sense to realise that our pain levels don’t always make the most interesting topic of conversation. We have had to learn to go about our lives whilst managing and living with pain. We don’t want fuss or sympathy, we just want to be normal, as much as this is possible. Constant complaining isn’t something we do. It gets me nowhere, it just brings me down….

Chronic pain sufferers have become expert at hiding their pain. We simply can’t spend all our time rolling around screaming, and we generally have the good sense to realise that our pain levels don’t always make the most interesting topic of conversation. We have had to learn to go about our lives whilst managing and living with pain. We don’t want fuss or sympathy, we just want to be normal, as much as this is possible. Constant complaining isn’t something we do. It gets me nowhere, it just brings me down….

You’ve done XYZ before, so why can’t you again?

A chronic pain sufferer may have managed to do something before, but at what cost? See the previous point about masking pain and not constantly complaining. Conditions can also change over time. Furthermore, facilities and services that are available to make life easier for people with disabilities, are not generally stuffed in our faces. We have to seek them out. And if we find them, we’re not going to say; “Oh well, I’ve managed with intense levels of pain before, so I’ll just carry on with that, rather than use a service that’s been specifically provided to help me.”

A chronic pain sufferer may have managed to do something before, but at what cost? See the previous point about masking pain and not constantly complaining. Conditions can also change over time. Furthermore, facilities and services that are available to make life easier for people with disabilities, are not generally stuffed in our faces. We have to seek them out. And if we find them, we’re not going to say; “Oh well, I’ve managed with intense levels of pain before, so I’ll just carry on with that, rather than use a service that’s been specifically provided to help me.”

No. Life with a chronic pain condition is hard enough, thanks. When I discover new ways to help manage my pain, I’m damn well going to use them.

We all have our aches and pains/I have a bad back too/similar comments ad nauseum.

I’ve had to listen to these types of comments a lot over the years, and they still really have the capacity to enrage me. Comments like this are so deeply insulting, and belittling of a person’s condition, and generally spoken with utter ignorance of said person’s condition and lived experience. Why assume to compare your own experience to that of someone else, when you have no fucking clue?

Would you say to someone in a wheelchair, “We all have mobility problems sometimes”?

Just, don’t.

These services are not for you/your type of disability

Erm, again, maybe possess yourself with a few facts. There’s no magic disabled card, that I’m aware of, that covers every disability service. We have to apply individually and specifically for eligibility to use particular services. I am not eligible for a blue parking badge, to use disabled parking bays, for example, because my individual needs don’t merit one (and as such I haven’t applied for one).

So if you see someone using a particular service, it’s probably safe to assume they have been assessed, and deemed eligible, and for good reason.

Kate, describes for Scope her experiences as a person with invisible chronic conditions,

As someone who deals with pain and fatigue, accessible toilets make my life easier. But many people assume they’re not for people with conditions like mine. There shouldn’t be a constant need to explain my chronic conditions to strangers. I need judgement-free access.

Another Morrissey fan describes her experience of using the disability access at a Morrissey show last year,

I have a not so invisible disability. I can stand (in immense pain) for the duration of a gig, but not queue as well. That would be far too long for me to stand, and my disability doesn’t enable me to sit on the floor. At one Moz gig I was stood 3rd row with my crutch, and was told by two people that I shouldn’t be standing at the front if I’m disabled. Yeah right, put all us cripples at the back out of sight why don’t you? Honestly it was awful. Luckily, I have great friends who supported me. But I’m going to get to the point that I will be physically unable to stand at the front one day, so I’m doing it while I can with my walking stick regardless of insults.

Facilities and services put in place for disabled people are about making our lives easier where possible, and striving to provide us with equal opportunities to those without any impairments. Here in 2023, I would have thought this was fairly well established and understood, but just to be clear, here’s a snippet from the Equality Act 2010, which places on providers of goods, services and facilities;

Facilities and services put in place for disabled people are about making our lives easier where possible, and striving to provide us with equal opportunities to those without any impairments. Here in 2023, I would have thought this was fairly well established and understood, but just to be clear, here’s a snippet from the Equality Act 2010, which places on providers of goods, services and facilities;

… a duty to make reasonable adjustments in order to avoid a disabled person being placed at a “substantial disadvantage” compared with non-disabled people when accessing services and facilities.

And just to be even clearer, equal means equal. That means people with disabilities should also be afforded an opportunity to stand at the front of a show if they so wish. The barrier is not reserved for able-bodied and young people who are fortunate enough to be able to queue. To suggest or assume so is blatant discrimination, and ableist privilege at its finest.

What’s wrong with you then?

Well, it’s not really any of your business. A person may choose to share with you the details of their condition, but that’s their choice, and not for you to ask. Questions like this are intrusive and frankly, rude. We’ve already had to share the minutiae of our medical details with the powers that be in order for them to determine our eligibility for a particular service you may see us using. It’s really not for you to question this.

Scope’s Attitudes Research of 2022 reports that;

Disabled people and their families experience a range of different attitudes and behaviours, such as:

- making assumptions or judging their capability (33%)

- accusations of faking their impairment or not being disabled (25%)

Making judgements, without being in possession of facts, isn’t a good look. Why accuse a person you see using a disability service of “faking it”?

But not everyone has been so overt with their accusations, and that’s what brings us to the subject of covert or subtle discrimination. Overt discrimination involves openly attacking or discriminating against someone because of their disability. Covert actions, however, involve subtle acts of preconception or prejudice.

“If we just look at overt discrimination, we are missing a lot of negativity that the targets of discrimination experience,” says Michelle Hebl, a professor of psychology and management at Rice University.

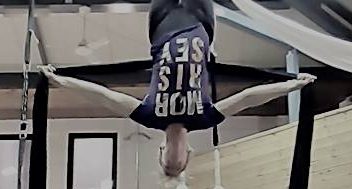

This appears to be the best way to describe the behaviour of some Morrissey fans, in response to my using the disability access at shows. Perhaps savvy enough to realise that it’s really not cool to bully someone for having a disability, or for using the disability services that they are entitled to, they instead invent other excuses to bully. Accusations, rumours and lies abound, and behaviour deteriorates to that akin to a school playground. Despite all five venues I have used so far giving priority access to disabled people, I am somehow accused of running past overnight queuers, turning around and staring/smirking at people once inside (turning around and leaning back on the barrier periodically is something I have always done, it’s one of the ways I manage my pain levels), and taking a centre barrier spot every night (also not the case). It seems I just haven’t done it right, or in an acceptable way. I am bewildered as to what that way might be.

Such covert discrimination may not be entirely conscious. Maybe people are not willing to admit, even to themselves, that this is what they’re doing.

But spin it whatever way you like, the bottom line is, some people either think I’m faking my needs, and/or view my priority access as an unfair advantage, rather than as a rightly provided reasonable adjustment, and attempt at levelling the playing field. The fact that my disability is invisible has been a huge contributing factor here. Did the visually impaired young lady at the barrier at Leeds Arena in 2020, for example, get accused of being a scammer? I doubt it. Did she get told she should be in the seats? I hope not, but nothing would surprise me anymore.

But spin it whatever way you like, the bottom line is, some people either think I’m faking my needs, and/or view my priority access as an unfair advantage, rather than as a rightly provided reasonable adjustment, and attempt at levelling the playing field. The fact that my disability is invisible has been a huge contributing factor here. Did the visually impaired young lady at the barrier at Leeds Arena in 2020, for example, get accused of being a scammer? I doubt it. Did she get told she should be in the seats? I hope not, but nothing would surprise me anymore.

Here’s a deal for you. If you think my Access Card gives me an unfair advantage, you can have it. I would be very happy to trade places with you. But along with this you also take my chronic pain condition, a condition that you will most likely have to live with for the rest of your life, and that will affect you not just at shows, but in so many areas of your life, and will impact on your ability to do the things you want to do, in so many negative ways. You think that’s an advantage?

I’ll finish with some thoughts from a fellow Morrissey fan who also has hidden disabilities;

Hidden disabilities or any hidden health and physical issues are hard to deal with, but even harder to deal with when people try to question it and ask for proof. You don’t know the constant pain that we have to live with every day, you don’t know how it affects our mental health and our everyday living and social life. Just because you can’t see it, doesn’t mean it isn’t there. I shouldn’t be made to try and prove it to you. Be kind and respectful as you never know what someone is going through.

And in Morrissey’s own words of course;

It’s so easy to laugh, it’s so easy to hate. It takes strength to be gentle and kind.

.

.

My experience of using the Access Card is shared here by UK disability charity, Scope.